By Li Dong

Dear Diary,

I got into a fight with brother today, so I ran away from the place he had me staying at. I wish I could go back home to mother and stay with her, but I’m not quite sure where she is staying or if mama is in trouble. I wish she would stop drinking but I don’t really know what she’s like when she is not drinking. Brother told me she began drinking after father passed. I have no memory of father and what kind of man he was, but I wish he was here to buy me something to eat. I did not think about being hungry or lost when I ran away, I was just so mad. Now I haven’t got any food to eat all day and no place to sleep. I’m tired and can no longer keep on. I would love some boiled pork and vegetable at this moment.1 I hope one day I’ll be able to eat whatever I wish.

Dear Diary,

I have suffered a great deal of trouble lately, but I’ve made a friend and I’ve got a plan for myself.

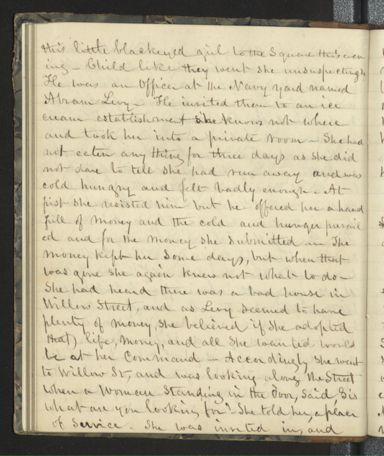

I met an older girl while I wander around looking for something to eat. She brought me to the square and I met an officer who bought me ice cream. He said his name was Levy. Abram Levy. I was careful not to let the officer know I had no supervision and had no home to return to nor that I had been wandering the streets cold and hungry. I was afraid he would take me away and lock me up if he found out, but he later let me go and gave me some money, though not without a shameful act in return.

In a few short days I was hungry again after the money had all been spent. Truth be told, I enjoyed having spending money and I wanted more money, more food, and board even if it means doing a bad thing, I suppose. I found my way to Willow Street and was taken in at Elizabeth Garrisons’ house for a fee I had to work for. Oh, how glad I am to no longer fear being taken away for sleeping on the streets.

Dear Diary,

I heard news that mother is in prison again. Brother said it was for drunkenness and I wonder if she had spent the money that I sent her way on rum. I wish I could keep mother out of trouble. I fear one day she will die of intemperance, and no one will help her or take the poor woman to the hospital.2 I fear that I will hear of her passing long after she is gone.

Dear Diary,

The madam showed me her new dress she got around Walnut Street. It’s a beautiful dress she had saved for a long time to get. She says the dress maker was trained in Paris and the dress is made of the finest French-imported fabrics.3,4 I long for the day I can get myself such a dress. When I save enough money, I’ll order a fine hat to go with my dress. When I can afford such luxuries, I’d go dine at a fancy restaurant, and order anything I wish to taste from the bill of fare.1,5

Dear Diary,

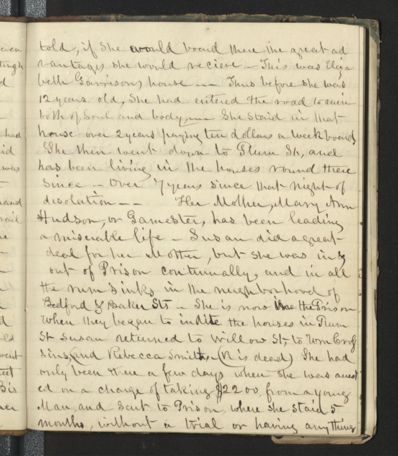

After seeing other women like myself being taken away to prison many times, the same fate had fallen upon me. Charged with taking twenty-two dollars from a man, though there was no proof, I was sent to prison. The nightwatchman saw me speaking to a man and found me at fault while the man was let go with not even a single word from the nightwatchman. For five long months I sat in a small cold room and pondered my poor fortune. I did not harm no man nor woman. I did not speak foully. I caused no trouble to no one. Could it have been the paints on my face, marking me as a tainted woman of no good?6 I wonder what mama thinks about when she is hidden from the world. I must ask her when I see her next.

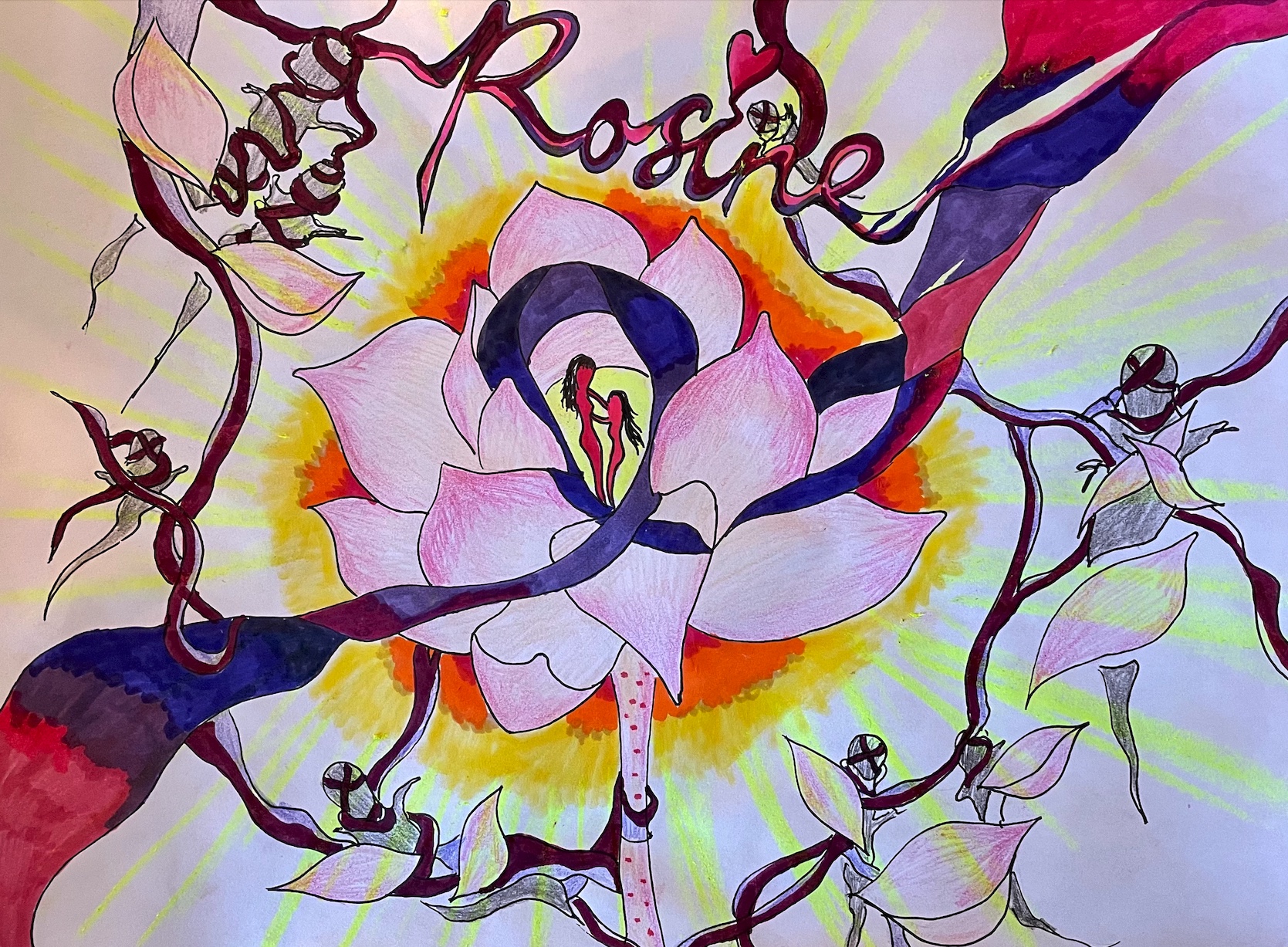

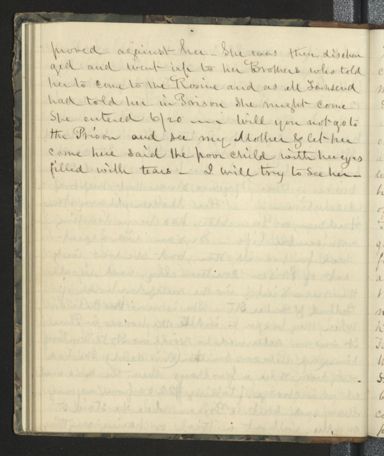

I found my way to the Rosine and they took me in. I asked the good people here to please get my mama to the Rosine too. She has been in and out of prison more times than I can remember, it must tear at her soul. I think it will do her good to be here. I wonder if mama will come meet me here. I miss her dearly.

Author’s Note:

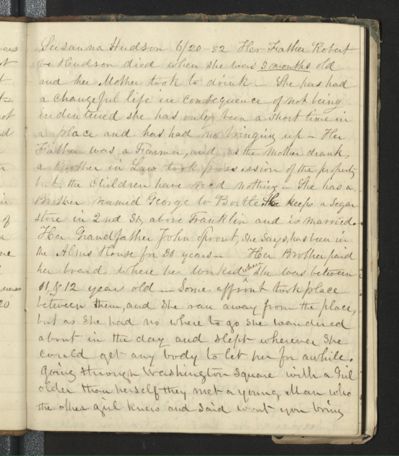

I chose to tell the story of Susanna Hudson through diary entries I imagined the young woman would write her thoughts and memories in like many people do when they were young. Susanna was a young teen during most of the years of her life that was described in the case file. She left home and pursued sex work as a means of survival before the age of 12. I wanted to highlight the innocence, desire, and care that remained in her being regardless of the sexualization and criminalization that she had been subjected to. Susanna Hudson did not choose “the road to ruin both of Soul and body” far before adulthood because of an innately rotten femininity7. She was a young girl that was hungry, cold, without a stable home, and looking to fulfill her needs and wants so I wanted to explore what those desires might’ve been for her. The case file did not go into what Susanna wanted money for and what kept her in sex work for seven years so I did some research on what some of the luxuries and trends of the time were, which inspired some of the diary entries.

Participating in sex work at such a young age at her own will is something that I have no intention of justifying as appropriate, but I also do not want to solely focus on Susanna Hudson’s victimhood as the case file has already done. Instead, through this project, I aim to envision the opportunities for joy and the hope of a better life that sex work could’ve potentially brought her, even if it were fleeting. Poor women are often recounted as passive victims of systems of injustice and inequality, but I wanted to add to the biography of Susanna Hudson not by reasserting her helplessness and depicting her as a distressed young woman, but by showing that she made the decisions she did to make the best of the conditions she was subjected to in the 19th century and how she lived through it.

The last part of her biography in the case file stuck with me because it demonstrated the Susanna’s care for her mother and an understanding of the sufferings her mother endured as her mother had been in and out of prison for drinking. While this biography was about Susanna Hudson, her mother’s life and experiences as mentioned throughout the case file shows that she had a significant presence in Susanna’s consciousness, which is also a reminder that she was a young girl who longed for her mother.

Will you not go to the Prison and see my Mother & let her come here said the poor child with her eyes filled with tears”7

Before arriving at the Rosine Association, Susanna had been imprisoned without a fair trial. I imagine that Susanna’s empathy for her mother grew after experiencing imprisonment herself and realizing how easily women could be punished for minor offenses. Her mother, poor and an alcoholic with no father or husband to claim her, was precisely the kind of woman that would be subjected to criminalization by “Constables and night watchmen [who] exercised tremendous discretion in deciding that certain women—those too poor, too loud, too sexual, too drunk, or too independent—did not deserve to be free.”8 Having been denied her own freedom for five months for taking money from a man and assuming that the man did not receive any punishment, Susanna must’ve recognized how precarious freedom was for women like her.

Whereas being out in the streets alone, drinking and any hint of overt sexuality was condemned for women, buying sex and drinking was acceptable for men and they would receive no punishment.8 The first man she had sexual relations with when she ran away was an officer who took advantage of her vulnerability especially since he was an authority figure that could’ve had her arrested. This detail in her biography show that not only did the criminalization of women’s sexuality make them more susceptible to being imprisoned, but it also made them more vulnerable to coercive sexual advances from men who exploited the gendered politics of criminality.

I hope that through the approach of diary entries, a multitude of emotions and a more multi-faceted narrative of Susanna Hudson is communicated. While there was pain and fear, there must’ve also been hope and agency.

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

ZH-CN

X-NONE

-

Pt. 2 -

Pt. 3 -

Pt.4 -

Pt. 1

Citations and Notes:

1Swiss Republic. Bill of Fare. Boston. 1853. https://victualling.files.wordpress.com/2019/07/entree1853swissrepublicboston.jpg

I referenced this restaurant menu to see what was commonly ate in the mid 19th century.

2Osborn, Matthew Warner. “A Detestable Shrine: Alcohol Abuse in Antebellum Philadelphia.” Journal of the Early Republic 29, no. 1 (2009): 101–32. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40208240.

Men who were alcoholics were more commonly diagnosed with “delirium tremens,” a disease that could be treated. Women, especially poor women’s alcoholism was more commonly labeled as “intemperance,” a way of defining one’s drinking habits and morality. Those labeled by the term “intemperance” were less likely to be sent to the hospital and treated for their alcoholism.

3Madame Gaubert. French Millinery, and Fancy Dress Making Establishment. Philadelphia. Between 1831-1834. https://librarycompany.org/fashioning/images/4.xam1831gaubert-14395-q.jpg

This primary source gave me an idea of what was popular and desirable in women’s fashion at the time.

4Mrs. Lehir. “Paris Millinery” from Byram’s Illustrated Business Directory. Philadelphia: J.H. Byram. 1856. https://librarycompany.org/fashioning/images/4.ldirphila1856-10231-q-p83.jpg

This is another primary source that shows french millinery remained popular two decades after the earlier source.

5American House, Hanover Street. Bill of Fare. Boston. 1851. http://menus.nypl.org/menu_pages/24659/explore

I wanted to look at another menu to get a better idea of the dining options and noticed that in the 19th century menus were called “bill of fare.”

6Peiss, Kathy. “On Beauty… and the History of Business.” Enterprise & Society 1, no. 3 (2000): 485–506. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23699594.

In earlier American history, makeup was associated with prostitutes and was not widely used by women who were considered virtuous.

7Rosine Association (Philadelphia, Pa.), Rosine Association casebooks, Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College, 2021, https://github.com/swat-ds/datasets/blob/main/rosine/rosine-transcripts/rosine_entry_148.txt.

8Jen Manion, Liberty’s Prisoners: Carceral Culture in Early America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015), 93.