By Diddy Vance

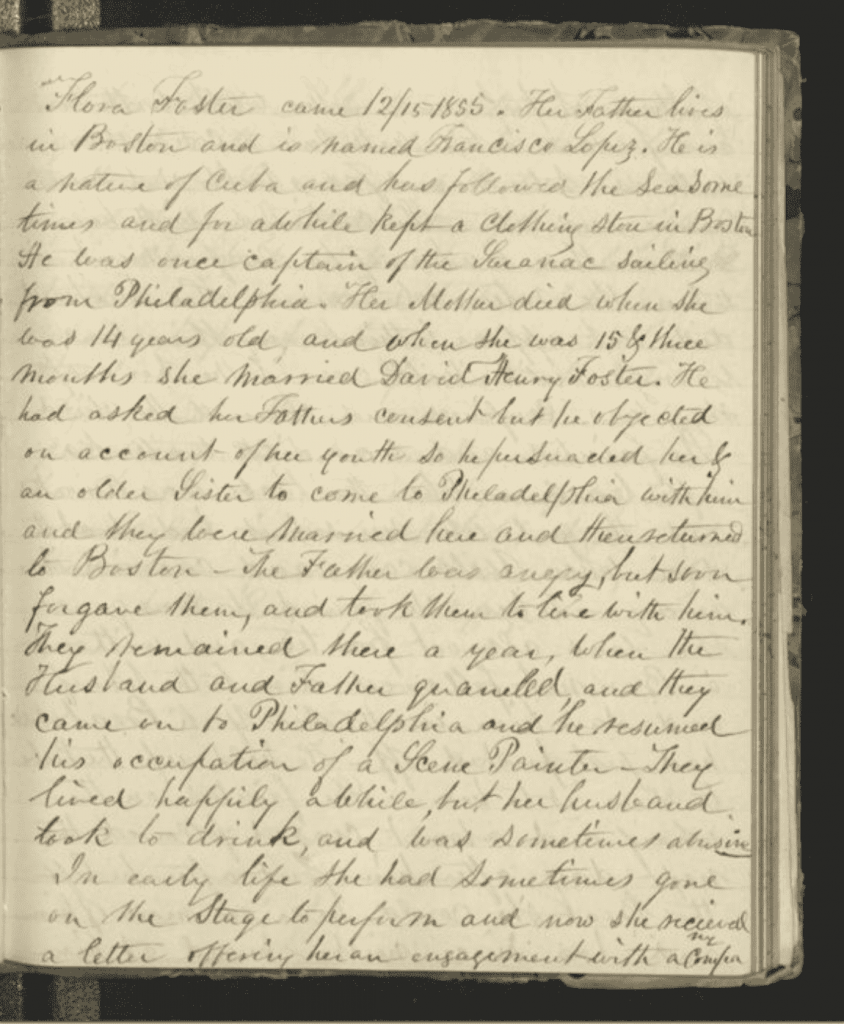

On December 15th, 1855, the Rosine Association became a safe haven for Flora Foster, a young woman who had been suffering from abuse at the hands of her spouse throughout their marriage.

I would like to start by noting that I refer to Foster as a “young woman” for continuity purposes, but in actuality, she is still a child when a few of the significant events mentioned occur. Flora Foster’s entry was of interest to me because of the intersections between race and gender that acted to worsen the struggles she faced in the 1850s. This piece was inspired by Sarah Haley’s “Speculative Accounting” that she uses in No Mercy Here: Gender, Punishment, and the Making of Jim Crow Modernity.[2] Because so little is known about Flora Foster outside of what she told the Rosine Association, I felt narrating her life this way would provide the most insight on her experiences.

Flora’s father, Francis Lopez, was a Cuban immigrant who worked numerous jobs to provide for Flora and her older sister.[3] Given that Lopez was living in Boston before any significant restrictions on immigration were put in place, he already saw difficulties trying to find work. As if that were not enough, Lopez spoke little English and his daughters saw the toll this took on him. After Flora’s mother died, she decided she wanted to marry a man named David Henry Foster[4], whether this was because she was in love or because he could provide her with economic stability is a question we will never know the answer to. Still, it can be assumed that Flora would alleviate some of her father’s stress by getting married. Flora and David needed Lopez’s consent to proceed with the marriage because she was only 15. When Lopez was unwilling to agree, David grew frustrated because he was always used to getting his way. Though David’s age is nowhere to be found, his power over her suggests that he was probably older than Flora by at least a few years. He convinced Flora and her older sister to travel to Philadelphia with him so that she could consent to their marriage in her father’s place[5]. This discourse between David Henry Foster and Francis Lopez highlights the loss of agency that Flora, and others just like her, experienced just by being a woman. Aside from that, the ability for a child to get married, even with parental consent, highlights that laws were not always there to protect individuals.

After they were married, Flora and David traveled home to Boston only to return back to Philadelphia around a year later[6]. Despite what could be viewed as a successful marriage by outsiders, Flora and David Henry were not as happy as they seemed. David Henry grew violent when he consumed alcohol, taking it out on Flora whenever he got the chance[7]. As historian Jen Manion writes in her book Liberty’s Prisoners, “Alcohol fueled tensions between friends, lovers, and strangers and was blamed for a high number of assaults.”[8] This could be the reason no one thought anything of the abuse Flora was forced to endure, or maybe she just hid it well. Eventually, Flora grew sick of the mistreatment and made the decision to join a group of traveling performers.[9] Flora loved performing, she was a natural on stage and knew she had potential to go far. She began thinking that this might be a way for her to escape David Henry and take care of herself.

Sadly, that dream did not last long. While she was traveling, Flora began a relationship with James Webb.[10] He made her happy, and Flora even thought about leaving her husband for him once they arrived back in Philadelphia. Not too long after she returned home, resuming her relationship with David Henry, Flora received shocking news that she was going to have a child.[11] Flora was fearful of raising a child with David Henry because of his abusive tendencies, but she believed he was the better choice over James Webb.

Flora’s child made her life worth living, she dedicated all of time to caring for her daughter and wanted nothing but the best for her. With David Henry working everyday, Flora thought that she could continue living like this as long as she had her child. Before her daughter had even turned a year old, James Webb showed up at Flora’s house and took the baby from her.[12] Panicking because she knew that she would never see her daughter again if she let him go, Flora chased after Webb, screaming and crying as she watched him get in a boat with their child and flee.

Flora was devastated, her daughter had been the reason she stayed with David Henry. She wanted to ensure her child had a better life than she did, and James Webb ripped that away from her. Flora had always been the one caring for their daughter, the only thing she could think about as she traveled home was how unprepared Webb was to raise a child. He knew nothing about their daughter, which only worsened Flora’s anxieties. Regardless of her newfound hatred of Webb for taking her child away, she did not want the girl to suffer just because he was a poor father. She was overwhelmed with emotions by the time she returned home from looking for her kid one last time, but David Henry did not seem to care how she felt. He was antagonistic, trying to start a fight before she even made it through the front door. Flora knew she had to leave when he slapped her across the face while they were still outside.

Soon after her departure, she made a friend that was familiar with working on the streets. Clara Norris acted as Flora’s guide around Philadelphia and took her to a place she thought she could stay.[13] Norris, however, was unaware that Flora had no money to cover rent, which meant she was going to have to find a way to make money. Flora was amongst the many young women who “turned to prostitution to support themselves.”[14] Though it was not as she had originally wanted, prostitution was better than returning back to an abusive husband who only served as a reminder of her stolen child. After a few months passed by, Flora was shocked to see her husband on the street corner where she typically worked. He was extremely apologetic, talking about how he had been miserable while she was gone and he needed her back in his life. As he apologized, she thought about how horrible the past 8 months had been, constantly worried she would become diseased or end up in jail. Flora was convinced David Henry was truly sorry and returned home with him.[15] David Henry fell back into his old habits not too long after their reconciliation, drinking more than he had in the past and becoming even more aggressive. Within a month, Flora found herself at the Rosine Association.[16] It was not her initial plan to go there, she was not even sure where she was headed when she left her home on that cold December evening. The Rosine Association was there for Flora Foster when no one else was.

1. Rosine Association Casebook, 1851-1858, Mira Sharpless Townsend Papers, In Her Own Right, Swarthmore College, 177. https://digitalcollections.tricolib.brynmawr.edu/object/sc152357#page/177/mode/1up.

2. Haley, Sarah. No Mercy Here: Gender, Punishment, and the Making of Jim Crow Modernity. University of North Carolina Press, 2016. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5149/9781469627601_haley.

3. Rosine Association. “Rosine Association Casebooks.” Philadelphia, PA, June 21, 2021. Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College. github.com/swat-ds/datasets/blob/main/rosine/rosine-transcripts/rosine_entry_234.txt.

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. Manion, Jen. Liberty’s Prisoners: Carceral Culture in Early America. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015, 86.

9. Rosine Association. “Rosine Association Casebooks.” Philadelphia, PA, June 21, 2021. Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College. github.com/swat-ds/datasets/blob/main/rosine/rosine-transcripts/rosine_entry_234.txt.

10. Ibid.

11. Ibid.

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

14. Wendy, Woloson A. “Selling Sex.” Capitalism by Gaslight: The Shadow Economies of 19th-Century America. https://librarycompany.org/shadoweconomy/section4.htm.

15. Rosine Association. “Rosine Association Casebooks.” Philadelphia, PA, June 21, 2021. Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College. github.com/swat-ds/datasets/blob/main/rosine/rosine-transcripts/rosine_entry_234.txt.

16. Ibid.