By Serena Yang

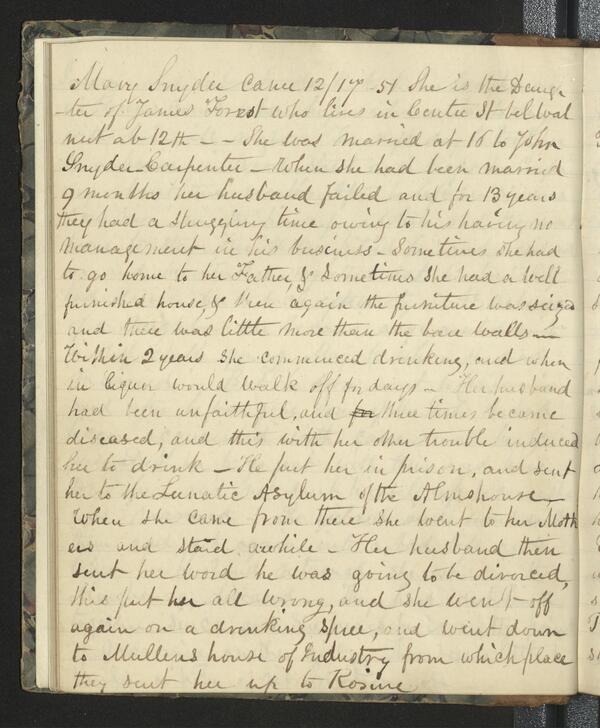

Mary Snyder was in her early thirties when she arrived at the Rosine on December 17th, 1851. By that time, Mary, who married at 16 years old, had spent more than half of her life in a deeply troubled marriage. Despite infidelity, disease, financial hardship, and incarceration, Mary remained married to her husband John Snyder Carpenter for over a decade. She began drinking less than two years into their marriage.1 Throughout her entire life, Mary passed from one form of patriarchal control to another, and when these patchwork intimate patriarchies failed, the state’s carceral institutions stepped in. Her marriage, no matter how turbulent or unhappy it was, was the primary intimate relationship that Mary’s personhood was founded upon. When she received news that her husband intended divorce, she went on the drinking spree that would eventually lead her to the Rosine Association.2

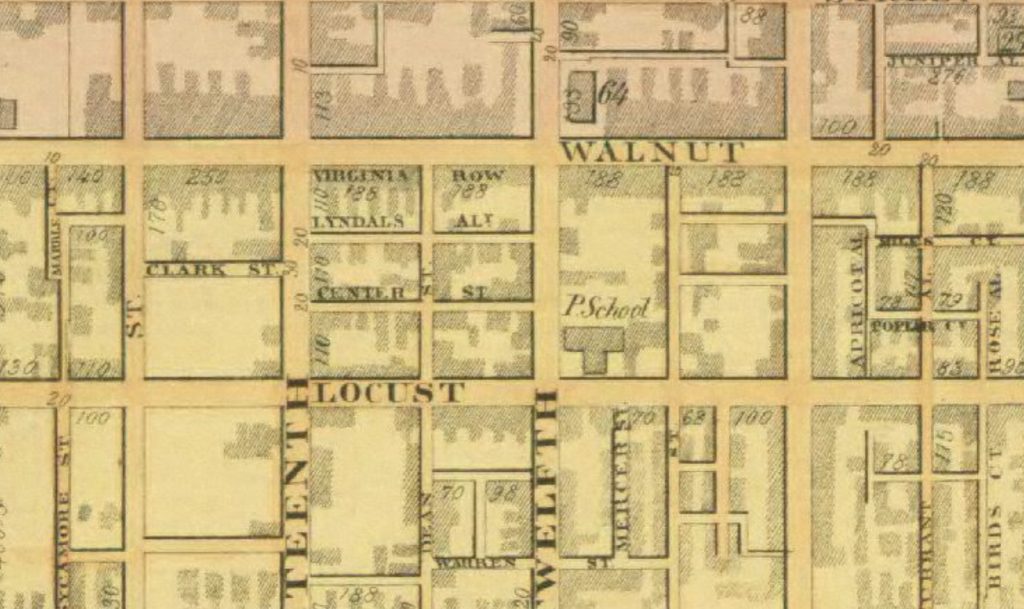

Expectations of normative female domesticity limited Mary’s life chances from the beginning. Born to a “respectable” family who lived in center Philadelphia a block away from bustling Broad Street, Mary’s chances appeared better than most.3 Under a system of intimate patriarchy, society was organized around the standard unit of a family made up of dependents––wives, children, servants, and slaves––under the control of a male head of household.4 Mary’s role was to legitimize the authority of her husband by depending on him to manage public matters such as earning a living.5 However, nine months into their marriage, “her husband failed” to manage his business, and they fell into difficult times for the next thirteen years.6

Like other 19th century Philadelphians, Mary’s husband faced a “shifting political economy” that increasingly relied on wage labor and led to widespread poverty. Women like Mary, excluded from formal participation in the political economy, were punished for being unable to carry out their domestic responsibilities when husbands failed to fulfill their public ones. Intimate patriarchy held onto its diminishing claims to legitimacy through the criminalization of dependents appearing to be “masterless” in public.7 Women on the streets who could not be “spoken for” by respectable men were subject to scrutiny and incarceration.8 Women who refused––or were unable––to “labor in the domestic realm as someone’s wife or dutiful daughter” were charged as disorderly, idle vagrants.9

Under this system, Mary was left with few choices. She was responsible for keeping a “well furnished house,” but when her husband’s business failures meant that “the furniture was seized and there was little more than the bare walls,” what could she do?10 If she sought work in the informal economy, she would have been seen as “a social nuisance” and subjected to harassment and arrest by watchmen.11 If she didn’t, financial hardship would make it impossible for her to be a dutiful wife. If she left her husband or her husband left her, Mary would become “masterless.” The new social order and political economy meant that women were more free than ever before to “leave husbands who were abusive, controlling, or undesirable,” but if they did so, they could “[find] themselves facing impossible economic obstacles in single life.”12

Prison became a way to “cover up” the significant weaknesses of this new political economy.13 A wide array of carceral institutions involved in punishment, reform, and rehabilitation sprang up to “get people off the streets, provide a false sense of social and economic stability, and shift the blame onto the poor.”14 Mary passed through the doors of several of these institutions before entering the Rosine House. When she took up drinking, her husband “put her in prison, and sent her to the Lunatic Asylum of the Almshouse.” Other times, she would “sometimes go home to her Father.”15 She had just returned to stay with her parents when the news of the divorce came, upon which “a drinking spree” sent her to the Mullens House of Industry and then to the Rosine.16

The almshouse, the asylum, and the hospital existed alongside the newest innovation––the penitentiary––as “a continuum of institutions that advanced the state’s effort to establish order and assert greater social control in the unstable decades of the early nineteenth century.”17 These apparatuses of control, designed as safety nets or confinement for the sick and poor, were more similar in practice than their stated purposes may suggest. Philadelphia’s Blockley Almshouse, which opened in 1835 and may have held Mary Snyder at one point, included a lunatic asylum that later collapsed in 1864. The New York Times reported via the Philadelphia Inquirer that the building “set apart for the females thus afflicted” killed at least sixteen women when it collapsed. The article notes that “The Police of the Twenty-fourth Ward were on duty within the Almshouse the entire day, guarding the different doors and avenues in order to check any wild or excited acts on the part of any of the inmates, particularly the insane.”18 Carceral ideas were woven into the design of asylums and almshouses. Female inmates were punished for challenging authority, deemed “worthless huss[ies]” and “drunken nuisance[s],” and “sent to the cells for returning to the almshouse intoxicated.”19 Mary’s life in the almshouse would not have differed much from her life in the prison.20

Another institution Mary found herself in, the Mullens House of Industry, was founded by prison reformer William James Mullen’s Philadelphia Society for the Employment and Instruction of the Poor “for the purpose of supplying discharged convicts and other destitute persons with a home where they could be cared for and assisted to get employment.”21 Mary may have sought out the House of Industry as a means of securing financial independence, but again her options were limited and she was sent to the Rosine. Neither the prison, the asylum, the almshouse, nor the house of industry freed Mary from the grip of intimate patriarchy; they only succeeded in cycling her along to the next carceral institution, the latest of which happened to be the Rosine.

The Rosine Association was founded in response to critiques over the Magdalen Society’s approach to reforming “fallen women.” Unlike the Magdalens, the Rosine was managed and supervised by women instead of men and focused its teachings more on vocational training than Christian penance.22 Still, the Rosine maintained its precursor’s original purpose of serving women who were thought to have strayed from a path of virtue. The Magdalens chose women worthy of their charity by measuring them against a subjective femininity best embodied by women who had been failed by intimate patriarchy. Women who came from reputable families and were abandoned by their parents or irresponsible husbands were seen as unfortunate outliers of an otherwise effective system, and therefore especially reformable.23 This standard of judgment served to fill in the gaps of intimate patriarchal control; in doing so it reinforced instead of challenged the legitimacy of the larger structure.

Together, these institutions of punishment, rehabilitation, and containment formed a revolving door of carcerality. They also constitute the only surviving record of Mary’s life, making it difficult to imagine her personhood outside of the carceral structures that defined her in a particular way. Intimate patriarchy made Mary Snyder illegible unless under the custody of her husband, parents, or the state. Did she stay with other women when she “would walk off for days”? Who did she go drinking with? Did she turn to other intimate relationships for support?

It is possible, perhaps even likely, that Mary found transgressive forms of intimacy during the unrecorded hours she spent away from her abusive marriage, including her time as an inmate in the prison or asylum. Prison was often the only chance for inmates to interact with one another outside a domestic sphere controlled by patriarchs, employers, and masters, and a public patrolled by watchmen and constables. “In prison, inmates refused to work, plotted their escape, formed close bonds, shared stories, skills, and secrets, had sex, and nursed those who were sick… Out from under the watchful eye of a parent or master, an inmate might find it easier to enjoy friendship, community, sex, or other forms of intimacy.”24 Though these aspects of Mary’s life would not have seemed important to the reformers who recorded her biography at the Rosine, these alternate intimacies may have been essential to her survival.

Ultimately, whatever reprieve Mary may have fought to secure on her own would have still been ensconced in a hermetic web of carceral intimacies. After all, her husband, despite his own economic failings, had the power to institutionalize Mary at his will. The most consequential intimate relationship in her life was interlocked with carceral infrastructure. Each reinforced the other. The reciprocity of these systems of control makes it an essential and transgressive act to attend to the lives that slip through the cracks with care and imagination. Women like Mary became invisible in the moments when they slipped outside of both the sphere of intimate patriarchal control and the sphere of the carceral state, but by reading between the lines, we can imagine the many ways in which they resisted and endured under carceral patriarchy.

No records of Mary Snyder’s life after the Rosine are available. The Rosine Association differed from the Magdalen Society in its methods and philosophy, but it is hard to say whether they were more successful in securing a better life for the women they served. Moreover, what would the relative success of a more benevolent, fair, and humane enforcer of the existing social order even mean for a nation founded upon the defense of an unequal, contested citizenship?25 Any analysis of criminal reform that does not consider the carceral space as a particular configuration of the oppressive forces that extend far beyond any prison, asylum, or poor house’s gates will fall short. To Mary and others like her, it may have seemed as if at the end of every possible choice lay some form of unfreedom. It follows, then, that their every transgression was also an assertion of agency, personhood, and protest against a vast machinery of social differentiation, manipulation, and restriction.

Footnotes:

1. Friends Historical Library.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Manion, Liberty’s Prisoners, 77.

5. Ibid.

6. Friends Historical Library.

7. Manion, 78.

8. Ibid., 90.

9. Ibid., 91.

10. Friends Historical Library.

11. Manion, 91.

12. Ibid., 79.

13. Ibid., 6.

14. Ibid., 6-7.

15. Friends Historical Library.

16. Ibid.

17. Manion, 4.

18. “THE DISASTER IN PHILADELPHIA,” the New York Times.

19. Manion, 89.

20. Ibid.

21. Mullen.

22. Conn.

23. Manion, 95.

24. Ibid., 7.

25. Ibid., 195-6.

Bibliography

Conn, Marie. “Magdalen Society,” The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia.” https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/magdalen-society/ (accessed February 24, 2022).

Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College. Rosine Transcript 135, Rosine Association Casebooks, Mira Sharpless Townsend Papers. Philadelphia, PA. https://github.com/swat-ds/datasets/blob/main/rosine/rosine-transcripts/rosine_entry_135.txt.

Manion, Jen. Liberty’s Prisoners: Carceral Culture in Early America. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015.

Mullen, William James. “Seventeenth Annual report of William J. Mullen, Prison Agent,” January 1, 1871. Philadelphia, PA: State Library of Pennsylvania. https://archive.org/details/annualreportofwi00mull_0 (accessed February 24, 2022).

“THE DISASTER IN PHILADELPHIA.; Particulars of the Falling of the Walls of the Blockley Alms-house Lunatic Asylum.,” The New York Times, July 22, 1864. https://www.nytimes.com/1864/07/22/archives/the-disaster-in-philadelphia-particulars-of-the-falling-of-the.html (accessed February 24, 2022).