By Lily Fournier

The life of Julia McDonald, as documented by case workers at the Rosine Association, provides a window into the frustration and despair of 19th century women who attempted to live outside of the domestic sphere prescribed to them. Born in the 1820s and orphaned at an early age, McDonald attempted to create independence through work in and around theaters in New York City and Philadelphia. Within the thespian world, McDonald worked as an actress and, likely, as a sex worker.

Nineteenth century theaters were entangled with prostitution and other perceived vices. Entertainment districts in Boston and New York included brothels, taverns, gambling halls, and theaters.[1] Beyond the geographic proximity, theaters counted on prostitutes to bring paying customers and often gave these women discounted admittance rates.[2] Theaters in urban areas across the United States also regularly gave prostitutes free reign of the “third tier,” sometimes called the “gallery.”[3] These third floor balconies were home to some of the cheapest seats in the theater and provided limited privacy that sex workers used with their clients used to “exhibit their shamelessness.”[4] In later years sex work in balconies moved into even more brazen locations including the very public theater pit.

Theaters, from the stage to the third tier, provided opportunities for women to exist outside the confines of 19th century domesticity. Successful actresses in the 19th century were afforded both economic and social independence and social acceptance.[5] Perhaps Julia McDonald found herself drawn to acting for the independence and mobility it provided. Closely involved with theaters as an actress, McDonald would have been familiar with the gallery and the sex workers, and it seems likely she turned to sex work to support herself when acting alone was insufficient. By age 17, McDonald had been “seduced by the Manager of the [New York Theatre],” a perceived failure by the world and the reformers. Despite this fall from grace, however, McDonald continued to work sporadically as an actress, supplementing that work with time spent in “houses of ill fame.”[6]

Within theaters, McDonald also likely came across reformers and reform efforts. Through the 1830s and 40s theaters were the target of Christian reformers. These efforts saw the theater itself as “morally corrosive” and cited the proliferation of sex work as irrefutable evidence of theater’s moral sin.[7] In response to the hostile political environment, theaters themselves embarked on reforming efforts to clean up their establishments and save their stages from reformers’ crusades. In Boston and Providence, theaters were constructed without a third tier and owners and operators attempted to reorient theaters toward acceptable business and upper middle-class patrons.[8]

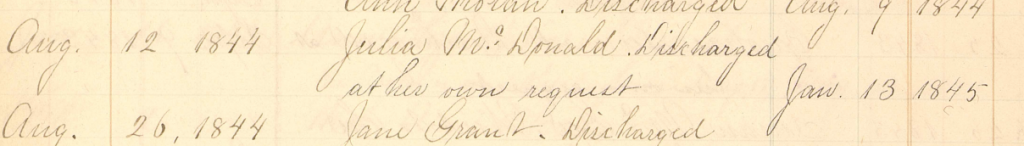

Involved in a villainized profession and inundated with reformers’ rhetoric of sin, McDonald repeatedly attempted to reform herself. She came to the Philadelphia Magdalen Association from the New York Magdalen on August 12th, 1844. Magdalen associations, including the one in Philadelphia were founded to reform prostitutes and served women who wanted to “change their lives, repent, and find their way back to a more ‘’honest’ way of life.”[9] Only a few months after entering the Philadelphia Magdalin, on January 12, 1845,[10] McDonald discharged herself and “returned to the same abandoned form of life.”[11] In 1847, members of Philadelphia’s Rosine Association succeeded in convincing McDonald to attempt to reform herself by becoming a charge of the Association.

But what did reform mean? A reformed life available to Julia McDonald was difficult, dull, and tiresome. Orphaned as a small child, McDonald would have lost the stability and economic means that may have been available to her through her “Irish Gentleman” father.[12] Reformers in the 19th century were not concerned with improving the material conditions of prisoners, sex workers, or others discarded by society. Instead, many reformers believed that people “brought poverty on themselves, in part by failing to embrace a heterosexual nuclear family with a clear, gendered division of labor.”[13] The Magdalen Society trained fallen women in domestic arts that would allow these women to be “placed at service in a religious home, married off, or reconciled to their parents.”[14]

This trapped many women in a cycle of “poverty and imprisonment” that moved them in and out of prisons and almshouses.[15] McDonald followed this pattern, often attempting to conform to the strict social order by working at various times within the expected range of domesticity and wage labor. These periods of confirmation were interrupted by re-admittance to almshouses, charities, or prisons and a return to “an evil course of life.”[16]

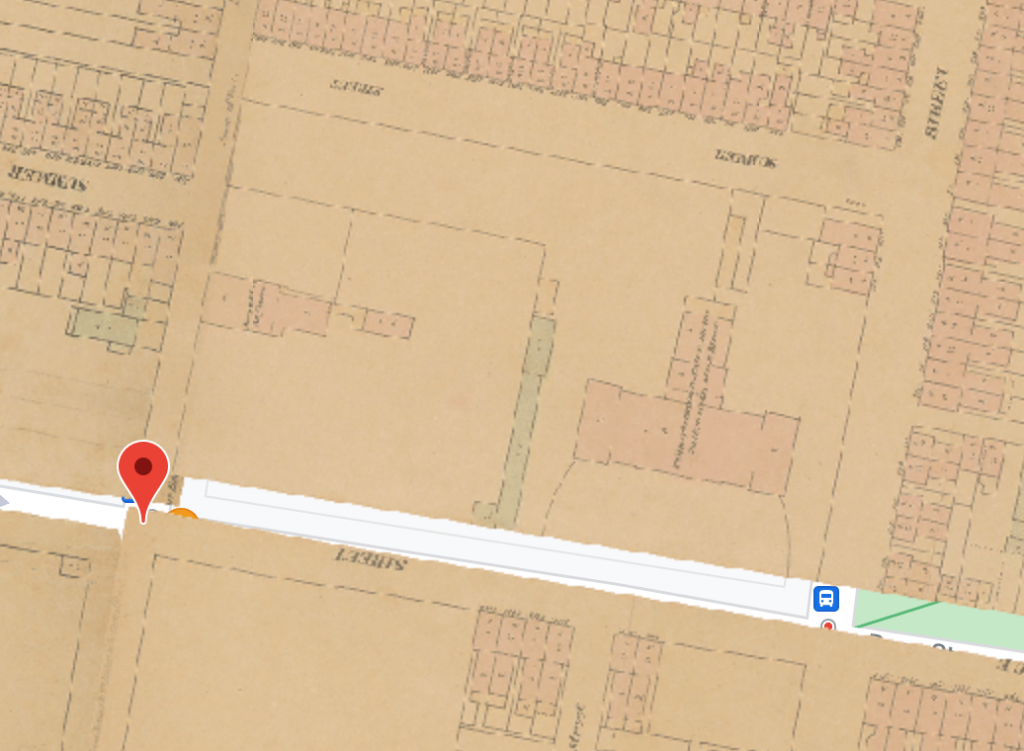

In early America and through the 19th century, incarceration and policing became a dominant mode for social control. Reformers played an important role in this system, often identifying subjects for reform, like Julia McDonald, from local prisons. In these prisons, “Inmates would be forced to submit to the authority of the state,”[17] a parallel experience to the submission to dominant patriarchal and heterosexual social norm that reformers demanded. Julia McDonald was identified by members of the Rosine Association while she was imprisoned for vagrancy in Moyamensing Prison. Vagrancy statutes that proliferated during the early 19th century were “aggressively used to get women off the streets.”[18]

Reformers hoped to transform vagrant women into a feminine, submissive model that limited them to the domestic sphere: practicing and performing the role prescribed by the patriarchy. These life limiting choices hindered independence for even the wealthiest women. Julia McDonald, without economic or familial support, found performing femininity, as promoted by reformers, to be cumbersome. She had also accepted the principles of morality, sin, and vice espoused by reformers. McDonald saw herself without options; an acceptable life was too dreary while a life of vice was too immoral. In this impossible situation, McDonald killed herself with a lethal dose of laudanum. Before she died, McDonald is documented as saying, “I am going to sleep, and I shall awake in hell.”[19] These words indicate Julia McDonald’s complex understanding of her predicament and the anguish she felt trying to conform to the 19th century’s expectations of femininity without economic support or comfort. She decided it was preferable to subjugate herself to an eternity of suffering in hell rather than continue to suffer on earth.

We will never know all the intricacies of Julia McDonald’s life. The facts of her life have been reduced, in the historical record, to her perceived failures and untimely death. We will never know McDonald’s perspective on her own struggles nor her rationale for the decisions she made. Even through the narrow window provided by the reformers at the Rosine Association, however, we can see how McDonald struggled to perform the femininity expected of her. Julia McDonald was the very first case file from the Rosine Association and her tragic death and difficult life are evidence of the limits of reform. Despite McDonald’s frequent contact with reformers, she saw her life as impossible. Julia McDonald constantly strived to do what the world claimed was right, but her circumstances meant that fitting into strict bounds of femininity was so difficult that McDonald chose to die rather than continue to struggle.

Notes:

- Bertozzi, Sarah S., “Vicious Geography: The Spatial Organization of Prostitution in Twentieth Century Philadelphia” 20 December 2005. CUREJ: College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal, University of Pennsylvania, https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/15, 6.

- Johnson, Claudia D. “That Guilty Third Tier: Prostitution in Nineteenth-Century American Theaters.” American Quarterly 27, no. 5 (1975): 575–84. https://doi.org/10.2307/2712442, 577.

- Ibid, 577.

- The Library Company of Philadelphia. “Selling Sex.” Capitalism by Gaslight. https://www.librarycompany.org/shadoweconomy/section4_3.htm.

- MULLENNEAUX, NAN. “INTRODUCTION: The Ax and the Faint.” In Staging Family: Domestic Deceptions of Mid-Nineteenth-Century American Actresses, xi–xxii. University of Nebraska Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv80cbs4.5, xvi.

- Rosine Association Casebook.” Unpublished manuscript, 1848-1851. https://digitalcollections.tricolib.brynmawr.edu/object/sc152356#page/5/mode/1up, 6.

- Sara E. Lampert; “The Presence of Improper Females” Reforming Theater in Boston and Providence, 1820s–1840s. The New England Quarterly 2021; 94 (3): 394–430. doi: https://doi.org/10.1162/tneq_a_00903, 395.

- Ibid, 396.

- Manion, Jen. Liberty’s Prisoners: Carceral Culture in Early America. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015, 94.

- Magdalen Society of Philadelphia records of admissions and discharges, 1836-1886. https://omeka.hsp.org/files/original/119/169/16195.pdf, 19.

- Rosine Association Casebook.” Unpublished manuscript, 1848-1851. https://digitalcollections.tricolib.brynmawr.edu/object/sc152356#page/5/mode/1up, 6.

- Ibid, 5.

- Manion, 87.

- Ibid, 95.

- Ibid, 66.

- Rosine Association Casebook, 5.

- Manion, 62.

- Ibid, 86.

- Rosine Association Casebook, 6.