Click here to read a collection of poems inspired by Sarah Elizabeth Smith’s case file.

Artist Statement — A Discussion on Domestic Violence

This series of four poems and the symbolic drawing aims to enrich the audience’s understanding of the life of Sarah Elizabeth Smith who was a survivor of domestic violence and one of the women who was admitted into the Rosine Association in 1854.1 I used the technique of speculative accounting to provide a subjective scope into the life of Miss Smith with information that was omitted in the original case file. In particular, I aimed to amplify her voice in the context of domestic violence survivors in the mid-19th century who were completely silenced by the white patriarchal hegemony that emphasized the privacy of the family as a patriarchal social institution, hence, giving male heads of the families the “inherent privilege” to impose marital violence upon their wives and children without social or legal punishment.2

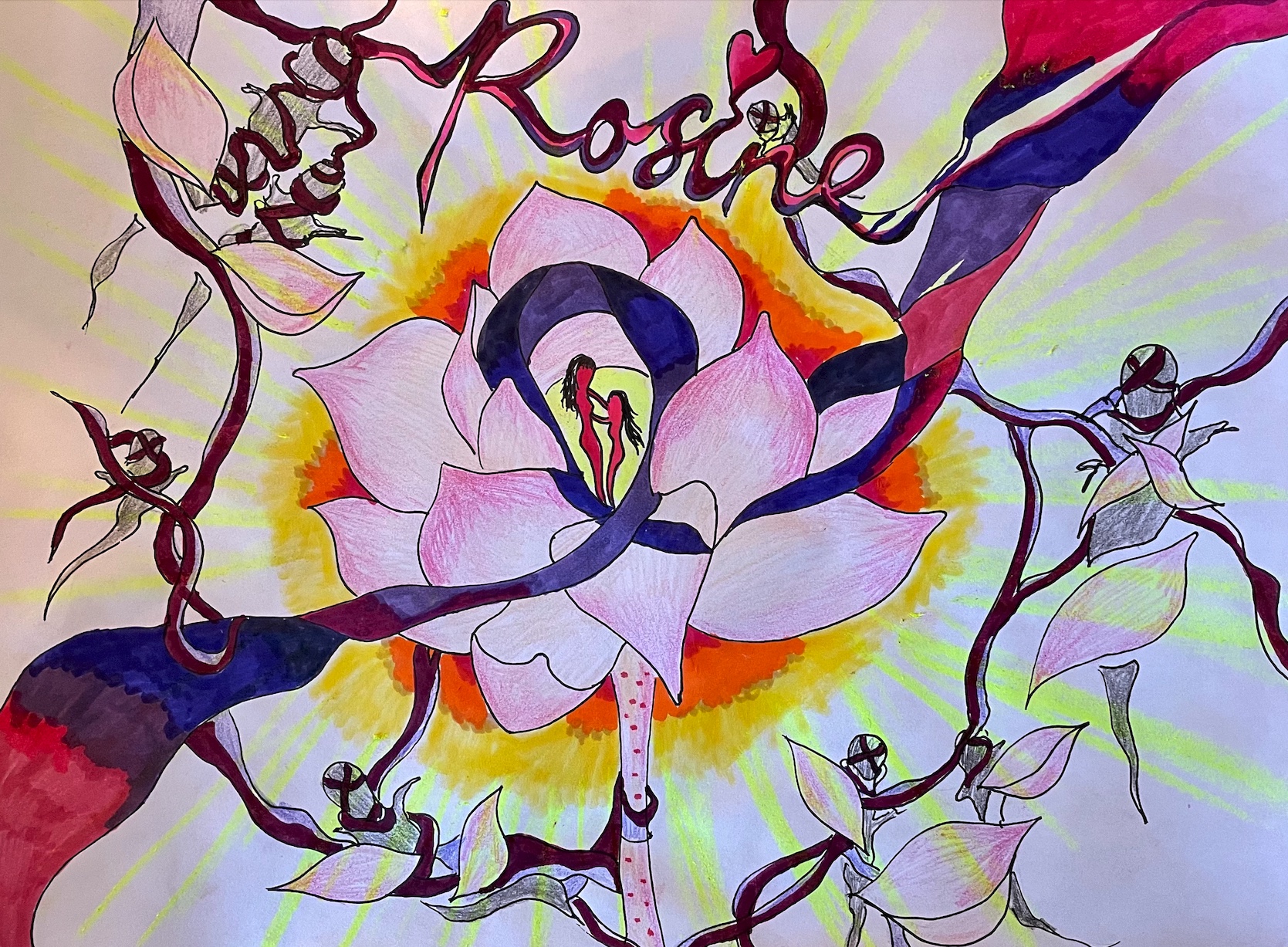

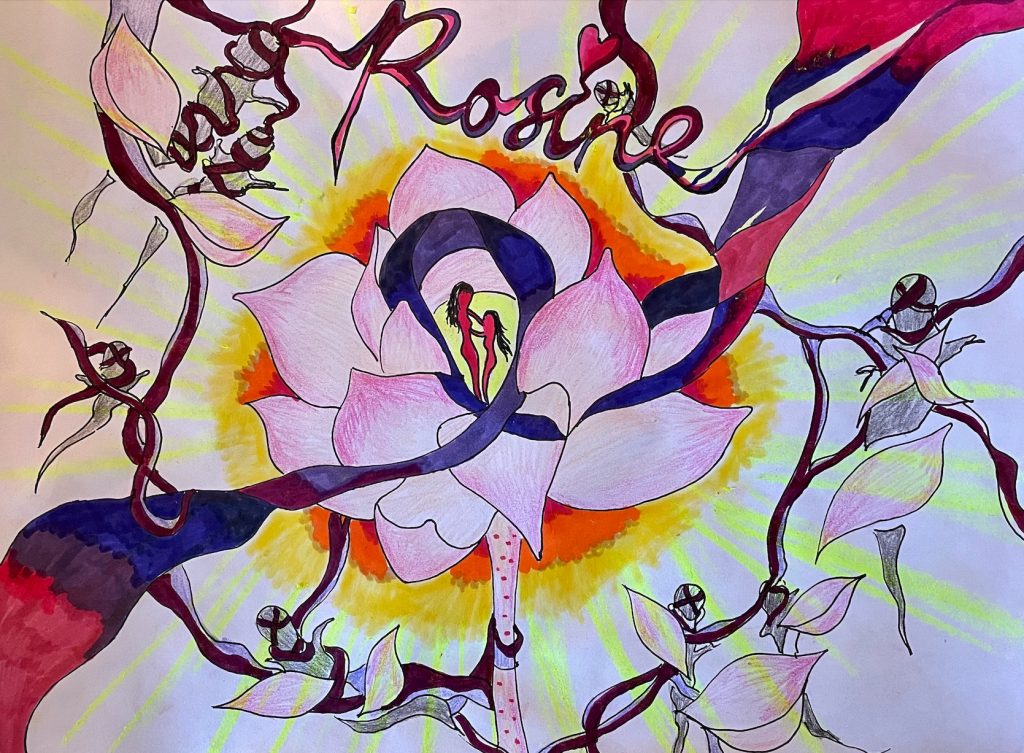

I acknowledge that although these narratives in prose are largely based on scholarly and historical sources, they are indeed speculative, subjective, and narrow in scope, meaning that Miss Smith’s life could contain many fringe circumstances that are not remotely close to my accounts. However, I tried my best to incorporate details after much careful consideration and analysis, for example, I incorporated research from Graunke’s article that discusses domestic violence paradigms for the Michigan Journal of Gender and Law, which states that many almshouses in the Philadelphia area have observed that young women who were domestic servants “were plagued with male employers and employer’s sons who had taken advantage of them sexually.”3 By taking consideration of how Miss Smith submitted to the sexual activity but ultimately left the house of her employer due to a “quarrel”, and the historical context of the stigmatization of adolescent sexual activity and the hypersexualization of domestic servants, I speculated that the younger son of the head of the household was the assailant and his parents’ discovery and arguments led to Miss Smith’s unemployment and homelessness4. Ultimately, I hope that the poems and the drawing assist each other in telling the story of the struggles of a young girl grappling with the loss of her father, the abuse of her stepfather, the helplessness of her mother, and the degradation of herself amid social challenges that are still relevant in our contemporary society.

The Rosine Association only temporarily uplifted certain women and helped them re-stand on solid ground and escape from the ghosts of their past. In contemporary society, domestic violence is still treated as a socially stigmatized “open secret” that should not be addressed at the forefront of our society, but should be kept in a private familial sphere until the women who were survivors have “the credibility” to prove their innocence and victimization in a public domain.5 These poems and imagery are deeply personal to me, and I urge the audience to be more aware of the ripple effect of domestic violence on single mothers and daughters contextualized in the mid-19th century and in our contemporary society. Comparing the 19th century to the current moment, what did not change is the repression of survivors’ power and silencing of survivors’ voices before, during, and after the violence and abuse, but the hope in the contemporary context lies in the self-advocacy of young women, the next generation of the daughters, through education, resistance, and activism. Domestic violence survivors who were at the Rosine Association and who are in current women’s shelters around the globe are rebirthing like the lotus flower, fighting against the ghosts of the abusive men in their past, step by step, towards liberation, hope, and a better future.

1 Rosine Association (Philadelphia, Pa.), Rosine Association casebooks, Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College, [June 21, 2021], [https://github.com/swat-ds/datasets/blob/main/rosine/rosine-transcripts/rosine_entry_214.txt].

2 Ruth H. Bloch, “The American Revolution, Wife Beating, and the Emergent Value of Privacy.” (Early American Studies 5, no. 2 2007), 245.

3 Kristi L. Graunke, “Just Like One of the Family”: Domestic Violence Paradigms and Combating On-The-Job Violence Against Household Workers in the United States, (9 MICH. J. GENDER & L. 131 2002), 138.

4 Charles E. Rosenberg, “Sexuality, Class and Role in 19th-Century America,” American Quarterly 25, no. 2 (1973), 137.

5 Bloch, “The American Revolution,” 235.

Bibliography

Bloch, Ruth H. “The American Revolution, Wife Beating, and the Emergent Value of Privacy.” Early American Studies 5, no. 2 (2007): 223–51. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23546609.

Graunke, Kristi L. “Just Like One of the Family”: Domestic Violence Paradigms and Combating On-The-Job Violence Against Household Workers in the United States, 9 MICH. J. GENDER & L. 131 (2002): 137-138.

Rosenberg, Charles E. “Sexuality, Class and Role in 19th-Century America.” American Quarterly 25, no. 2 (1973): 131–53. https://doi.org/10.2307/2711594.

Rosine Association (Philadelphia, Pa.), Rosine Association casebooks, Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College, [June 21, 2021],

[https://github.com/swat-ds/datasets/blob/main/rosine/rosine-transcripts/rosine_entry_214.txt].