By Karinna Papke

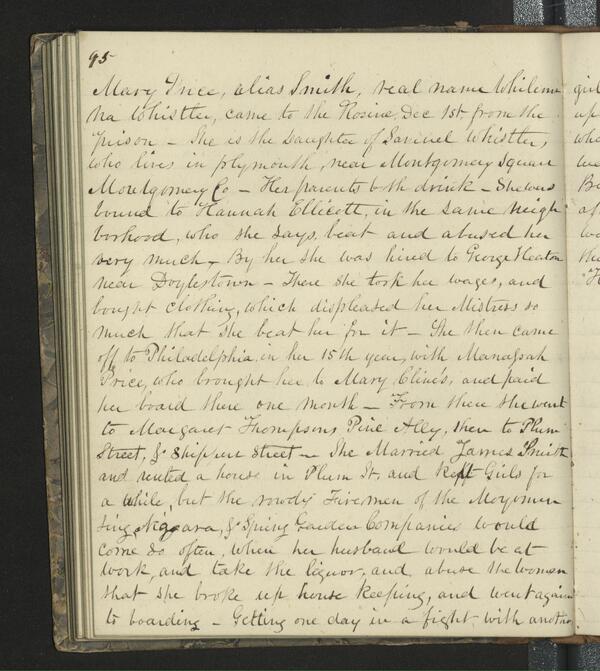

One of the only words used to describe Mary Price, whose birth name was Whilemena Whistler, in her case file created by the Rosine Association is “diseased.” In other words, it is difficult to paint a full picture of Mary Price’s life, especially when the only parts of it that are highlighted are related to her unorthodox upbringing and the “immoral activities” she is thought to have taken part in.

Mary was born in Plymouth Township, Pennsylvania. Her parents’ drinking habits landed her an abusive caretaker, Hannah Ellicott. After parting ways with Ellicott, she worked in a nearby town, and, again, faced abuse from the Mistress of the house she lived in. At the age of fifteen she moved to Philadelphia. Pine Alley, a street notorious for its brothels, quickly became her home.[1] Presumably, Mary became involved with sex work. She moved from street to street, until marrying a firefighter named James Smith. After tying the knot, she was tasked with running a house, under the alias of Mary Smith, that provided shelter for young women who were also thought to have been involved in sex work.[2] A Guide to the Stranger, a pamphlet that lists brothels throughout Philadelphia, contains an entry about a house run by a “Mary Smith.”[3] She is described as, “Being a mistress of a very good home.”[4] However, this source does not think highly of Mary, or other women involved in sex work. The introduction to the pamphlet notes that it was created specifically, “To warn the stranger and gay city bucks against the possibility of being involuntarily induced to visit a low pest house.”[5] Just as it appears that Mary had found some stability in her life, local firemen began to sporadically raid her home for alcohol while her husband was away. They also harassed her tenants on several occasions. The next major event that the file details is her arrest and imprisonment for fighting in the street. After spending two months in prison, she was sent to the Rosine Association. Only a week later she was shipped off to an Almshouse because she was characterized as diseased.[6]

There are several interesting aspects of this case file, from her absent parents to her stint in prison. At the same time, there are significant details left out of the two paragraph synopsis. Details that could humanize Mary and provide a better picture of who she was, aside from someone that society deemed a low life and relegated to places that were generally out of the sight of the public. For the purposes of this post, I will focus on how firemen were policed compared to female prostitutes, like Mary. I will also take a closer look at the idea that as women became more present in the public sphere, they were criminalized for actions, such as drinking and fighting. I will draw on Jen Manion’s book, Liberty’s Prisoners, to highlight the broader context of the mid-1800s and the ways in which time and place help explain the experience of Mary Price and the biases that those writing about and interacting with her viewed her with.

Though Mary continuously found herself in situations where she faced physical and emotional abuse, the case file fails to acknowledge the harm committed by her parents, caretakers, and various firemen. In particular, the rowdy firemen exemplify the contrast between how men and women were policed during the 1800s, as well as the ways that men’s desire to prove their masculinity led to violence against women. In the midst of industrialization, fire companies became more aggressive about asserting their group identity. According to Ric Caric, the author of “From Ordered Buckets to Honored Felons: Fire Companies and Cultural Transformation in Philadelphia, 1785-1850,” “For most companies, the focus on group identity meant a concurrent shift from fighting fires to fire company rioting and ritual as the most important fire company activities.”[7] Caric posits that in a newly “independent” American society, social groups strived to assert collective liberty and form local solidarities.[8] The structure of fire companies provided the perfect opportunity for men to form tight knit groups with distinct identities. Moreover, in the early 19th century, fire companies transitioned from fighting fires with buckets to hoses. While this may not seem like a significant change, companies had to recruit hoards of young men to maintain equipment and compete to fight fires. Additionally, firemen played an important role in reinforcing masculine and feminine stereotypes.[9] In the early years of post-revolutionary Philadelphia, they asserted their masculinity through physically dominating and harassing women, as they did to Mary. This was likely further perpetuated by the fact that they were not criminalized for their unruly behavior.

In contrast, as women became more prominent in public life, they were punished for their sexuality and other behaviors that were seen as inherently deviant when performed by a woman. In Liberty’s Prisoners, Manion makes this point by emphasizing that women were criminalized for breaking out of the domestic sphere and joining the workforce, often through selling stolen goods, alcohol, and their bodies. “Although physical violence was very much embedded in the framework of American national identity, women’s embrace of drinking, swearing, and strolling was seen as a telltale sign of the failure of republicanism’s vision for women.[10] Mary’s arrest and imprisonment for fighting in broad daylight supports the idea that women were punished for living their lives openly, and sometimes loudly, in a way that threatened America’s patriarchal society.

In addition to being sent to prison for fighting, Mary was stigmatized for her involvement in sex work. Though the case file does not mention her being criminalized for prostitution, which was often done using vagrancy laws, it does emphasize that because Mary was diseased, she was not fit to stay at the Rosine Association. In this context, being diseased likely meant that she contracted a sexually transmitted disease, presumably from her work. A Guide to the Stranger states that brothels are “low dens of infamy and disease.” [11] The source continuously uses demeaning language and stereotypes to describe women sex workers; it makes it clear that women who participated in sex work were wily, immoral beings who were not to be trusted. This sentiment was also prevalent among Reformers, including those who ran the Rosine Association. Their semi-annual managers report, published in 1851, calls attention to the fact that many women in society have deviated from the path of virtue, “Losing first her self-respect, then becoming indifferent to the opinion of others, casting off the restraints of decency and morality, and abandoning herself to a life of crime and shame.”[12] Mary exemplifies the life of a lower class woman, seeking economic opportunity and being looked down upon and pushed to the outskirts of society for doing so.

The story of Mary’s life as it is written by the Rosine Association paints a bleak picture of a woman who was able to escape a tumultuous childhood and find steady work to support herself. However, because her path to finding economic independence involved sex work, she was vilified. Though it is important not to extrapolate too much about Mary’s life, one cannot help but wonder about her day to day experience. Clearly she was skilled at finding her way independently through a large city and creating opportunities for herself. The Rosine Association’s description of her does not do her justice, but it does provide a snapshot of how women who defied social norms and participated in the informal economy were treated in the early years of industrialization. The file also allows the reader to directly compare how men and women were treated in the public eye. Mary was imprisoned for refusing to remain quietly in the domestic sphere. After being released from prison, she was stigmatized for making a living through one of the only avenues available to her. By holding a magnifying glass to Mary’s “wrong doings,” the Rosine Association gives us a better understanding of how the privileged few viewed the life and work of a poor woman trying to find her way in Philadelphia in the mid-19th century.

- Rosine Association (Philadelphia, Pa.), Rosine Association Casebooks, Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College, 2022, https://github.com/swat-ds/datasets/blob/main/rosine/rosine-transcripts/rosine_entry_088.txt, 96.

- Rosine Association Casebooks, 96.

- A Guide to the Stranger, or Pocket Companion for the Fancy: Containing a List of the Gay Houses and Ladies of Pleasure in the City of Brotherly Love and Sisterly Affection. Philadelphia, PA: Library Company of Philadelphia, 2015, 10.

- A Guide to the Stranger, 10.

- A Guide to the Stranger, 8.

- Rosine Association Casebooks, 97.

- Caric, Ric N. “From Ordered Buckets to Honored Felons: Fire Companies and Cultural Transformation in Philadelphia, 1785-1850.” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 72, no. 2 (2005): 117–58. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27778663.

- Caric, “From Ordered Buckets to Honored Felons: Fire Companies and Cultural Transformation in Philadelphia, 1785-1850,” 119.

- Caric, “From Ordered Buckets to Honored Felons: Fire Companies and Cultural Transformation in Philadelphia, 1785-1850,” 162.

- Manion, Jen. Liberty’s Prisoners: Carceral Culture in Early America. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015. 119.

- A Guide to the Stranger, 8.

- A Guide to the Stranger, 7.

- “Rosine Association Semi-annual Managers’ Report,” Mira Sharpless Townsend Papers, RG5/320, Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College, 1851, https://digitalcollections.tricolib.brynmawr.edu/object/sc152355.