Spirit weak, lodged between the crevices By Nancy Vu "She was the most pitiable, bloated, wretched looking creature." Her father, a cupper and bleeder Could not stop the bleeding of her heart and his very own spirit. Growing up, Catharine’s father filled himself with drink; At 14, the drink washed away their familial bonds. She was one to love, but unloved for her free spirit. She found new family when she married Frederick, A jeweler and a tainted gem himself. Their love was shared in brothels, dubbed “bad houses” To her mother’s disdain. With a new family comes new homes – places closest to the heart. At 17, Durham was left to shoulder the burden on her own, only 700 dollars and furniture in her poor mother’s name. Her home became cold – she fought with her partner until they separated, And she never turned back even when he asked for her to return. She was a bird whose wings were clipped before she could learn to fly. She became the sole supporter of her children; Her body became a subject for people to gaze For a few dollars, she became a tool for the desires of others, Not fit to sustain herself through “honest” labor. She was the subject of pity, of a hope lost too early Her work made her less than human, tainted and debased. Forced to drown in her sorrows with no prospect of recovery, She drowned herself in drink, The closest she could get to her father’s touch once more. She was a lonely spirit, walking streets no longer open to her. She walked through doors that led her out into the alleyways, A revolving door that drove her spirit crazy. For what felt like reliving the same nightmare a hundred times, Fiction and rumor became reality for her. She was so low, she began to feel she deserved the perpetual neglect Her habit of “racing the streets” became a lifestyle of its own She settled with a new man named Andrew McKean Clean as he was, he could not contain her wild frustration, As she grasped at his wallet like vines to raise herself to the surface. Her thirst for the streets could not be quenched, And her inner demons swallowed her like a ritual baptism. Three times, she played with her friends, carceral and McKean. By the third day, she was ready to rise from the dead, seated by her father And held by her mother, but her body fell weak, her spirit strong.¹ She was the most pitiable, bloated, wretched looking creature; She was a nameless subject who needed to be named.

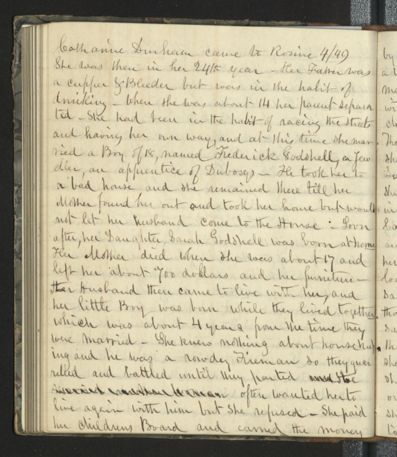

Page 1 of Catharine Durham’s entry in the Rosine Association’s casebooks.

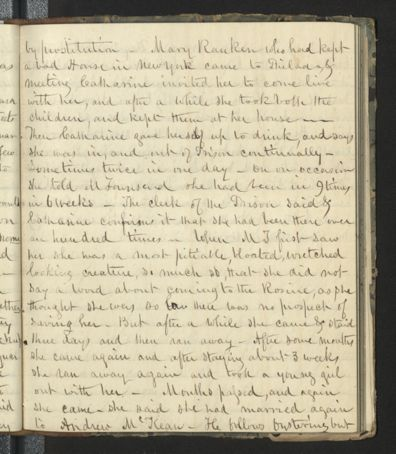

Page 2 of Catharine Durham’s entry in the Rosine Association’s casebooks.

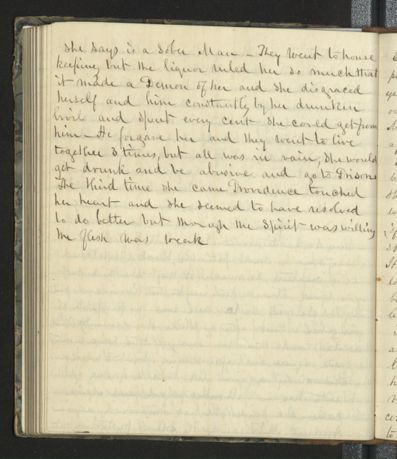

Page 3 of Catharine Durham’s entry in the Rosine Association’s casebooks.

Author’s note:

This piece is part of a collective effort to bring the story of often unnamed criminalized women to the surface while maintaining their agency and emphasizing their humanity. In particular, by reflecting on the intimate details of Catharine’s life prior to coming to the Rosine Association, I grant readers access to her motivations and the conditions that led her to her current position within the carceral system.

To start, I open the piece with details of her family background. This choice is significant not only for chronology but for deep analysis of her life leading up to incarceration. The family background of prisoners has been often cited as a crucial focal point and catalyst for their experiences with the carceral system in the long run.² In Catharine’s case, she witnessed the dissolution of her family and the downfall of both her parents (one to alcohol and the other to death) early on. This forces her to carry a heavy burden at a young age with little support through the mental difficulties of these traumatic experiences.

Further, I include the details of her economic situation to describe how her work in brothels and with prostitution to support her family sets her on the fringes of society at an early age. Sex work was morally condemned by people in society, and women were often dehumanized for participating in this form of informal labor, despite it being one of their few options for self-sufficiency.³ This reveals her vulnerability to ostracization by society and to the long-term effects of occupational limitations to her ability to command any sense of agency or respect for herself. Her dehumanization provides one explanation for her gradual decline, as she drinks to cope with the trials in her life. This then worsens her condition as she is continually involved with the carceral system with little to no prospect of change.⁴

Throughout this poem, I make several stylistic choices to tie Catharine’s experience with the general experience of female prisoners during this time. For one, I start and end the piece with the line “She was the most pitiable, bloated, wretched looking creature”, which is directly copied from her biography in the Rosine Association’s casebooks. I choose to repeat this line because it encompasses the general attitudes society had toward female prisoners of the time – by emphasizing their degraded positionality, they become not only subjects to be pitied, but subjects to be hidden.⁵ This is especially seen by her numerous run-ins with the carceral system for small crimes like drunkenness that remove her from society.

Similarly, I mimic the language of the time to speak on the ways criminality was seen as individual weakness within specific individuals. By using the term “spirit” repeatedly to describe her disposition, I frame her experiences as if they were experiences of intrinsic inferiority or debasement. Further, by describing some of her actions as “wild”, “free”, and “crazy”, I seek to highlight the various ways these prisoners were described as having a cultural (almost animalistic) “deficiency” that stood in opposition with white middle-class cultural values.⁶

The final 5-line stanza makes several religious references to stress the importance of religion during this time as a framework for American moral standards.⁷ However, by making religious references to detail her ultimate failure to re-enter society and stay in touch with the most intimate figures of her early life, I criticize the carceral system’s efficacy as a rehabilitative system and instead stress its role in further entrenching these women in oppressive conditions.⁸ The final line in this stanza follows directly from the casebook, describing how her efforts are ultimately futile because her health declines while her desire to escape the confines of the carceral system continues to grow.

Overall, I make an intentional effort to avoid the martyrization of Catharine as a figure of her time; rather, I focus on providing the context behind her life so that her crimes can be weighed with present social conditions, which often restrict women in their daily activities. I acknowledge that in parts of her life, the crimes she committed are morally unjustifiable. Still, the purpose of this work is to give her narrative a place in history, as her story is one that reflects many important themes regarding gender and incarceration during this time. This nuanced representation of her life provides a balanced narrative that neither justifies crime nor condemnation by society. This decision is made with reference to historian Kali Gross’s note on historiography in her book Colored Amazons and its uses to name and uplift historically marginalized groups without removing reality from their narratives or overly romanticizing their experiences.9

I choose poetry to tell Catharine’s story because its form can add more intimate detail and exploration of her life than a more practical retelling in a case file does. In this way, the reader can read Catharine’s story as one that reflects the vulnerabilities of women during these times. These case files present a limited perspective on the lives of these women, but through speculative storytelling in poetry, I am able to move closer to a narrative that describes their feelings with the stigmatization and dehumanization they faced under the carceral state for their involvement in the street economy.

1 This is a reference to Jesus’s resurrection after three days to sit on the right hand of God, the Father.

2 In Jen Manion’s Liberty’s Prisoners, the idea of the sentimental family often framed the way women pleaded for pardons, referencing their relation to their family and the consequences of children living in neglected home environments.

3 Chapter 3 of Manion’s Liberty’s Prisoners speaks on the way women from disadvantaged backgrounds are forced to choose between “the risk of imprisonment for stealing, the risk of disease from sex work, or the almshouse” for survival (Manion 2015, 85).

4 Chapter 3 of Gross’s Colored Amazons speaks on Sarah Palmer’s experience with the carceral system as a significant case, which has several parallels to Catharine Durham’s desire to change, inability to escape the carceral system, and ultimate downfall (Gross 2006, 80).

5 In class, we spoke about the role of prisons in society; one student made reference to the idea that prisons can be used to shield the common public from the depravity and abuse taking place within prisons, rendering these individuals invisible.

6 The introduction of Gross’s Colored Amazons speaks on how criminality became essentialized as something “inherent to all social others and in opposition to white middle-class cultural values” (Gross 2006, 8-9). This places “social others” in a position below the white majority while white citizens served as “social custodians” and reinforces a binary that privileges whiteness as pure and moral.

7 Gross’s Colored Amazons demonstrates how religion framed Western moral standards during this time; chapter 3 specifically describes how black female prisoners navigated these frameworks to uphold their position as “true women”, citing Christian morality as the pathway (Gross 2006, 92).

8 Historically, the US considered their implementation of the carceral system more “humane” compared to their European counterparts, emphasizing how their system allowed for prisoners to rehabilitate and reenter society as better people rather than face punishment.

9 Gross speaks on the problem historians often face regarding the martyrization versus condemnation of historically disadvantaged people of the time. In particular, the power of narratives comes from accurately representing events while acknowledging the social context being discussed.

General References

Gross, Kali. Colored Amazons: Crime, Violence, and Black Women in the City of Brotherly Love, 1880–1910. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006.

Manion, Jen. Liberty’s Prisoners: Carceral Culture in Early America. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015.

Rosine Association (Philadelphia, Pa.), Rosine Association Casebooks, Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College, 2022, https://github.com/swat-ds/datasets/blob/main/rosine/rosine-transcripts/rosine_entry_211.txt.